Necessity, as they say, is the mother of invention. Not that getting naked and sweaty and jumping into chilly water is truly necessary, but it can be a helluva lot of fun, not to mention a perfect way to meet girls.

Post-college years often lead to traumatic experiences like jobs with little hope for advancement and scant vacation time. Or the pursuit of mind-bending MBAs. For some, it’s the meandering and careless search of the meaning of life. Given the choices, I took the latter road.

It’s a proven scientific fact that sweating profusely then immersing oneself into icy water, especially after many days of alcohol consumption, is a guaranteed path toward total spiritual enlightenment. Just look at the Native Americans. They had it all figured out. Sioux Indians would regularly build their sweat lodges next to ice-cold rivers and make the sweaty plunge. They’d bend over some birch trees, cover them with buffalo skins, and toss a bunch of hot rocks from a bonfire into a hole in the ground. The peace pipe would go around with some finely chopped kanik-kanik and they’d chant their way into a full-on vision quest.

I know all this because I took the course in college. I’m serious. It was an anthropology class called Black Elk Speaks, named after the book. Part of the curriculum was building traditional Sioux Indian Sweat Lodges. It rendered two college credits and pretty much a guaranteed A, unless you were too prudish to prance around buck naked in broad daylight. At that point in my life, I’d have walked into the dean’s office with tassels on my nipples for an A, so going Full Monty in the woods with a bunch of other hippies in training was a no-brainer.

After college, our sauna-building intentions were perhaps less pure than the Native Americans, but they still led to a deeply spiritual journey nonetheless. The spirit of the seventies was still cranking along and the bloom of free love had not yet withered, even from the threat of AIDS, Jerry Falwell, and hard-core prudism. Girls still liked to dance around campfires to out-of-tune acoustic guitars, and we still liked watching them while we banged on our instruments.

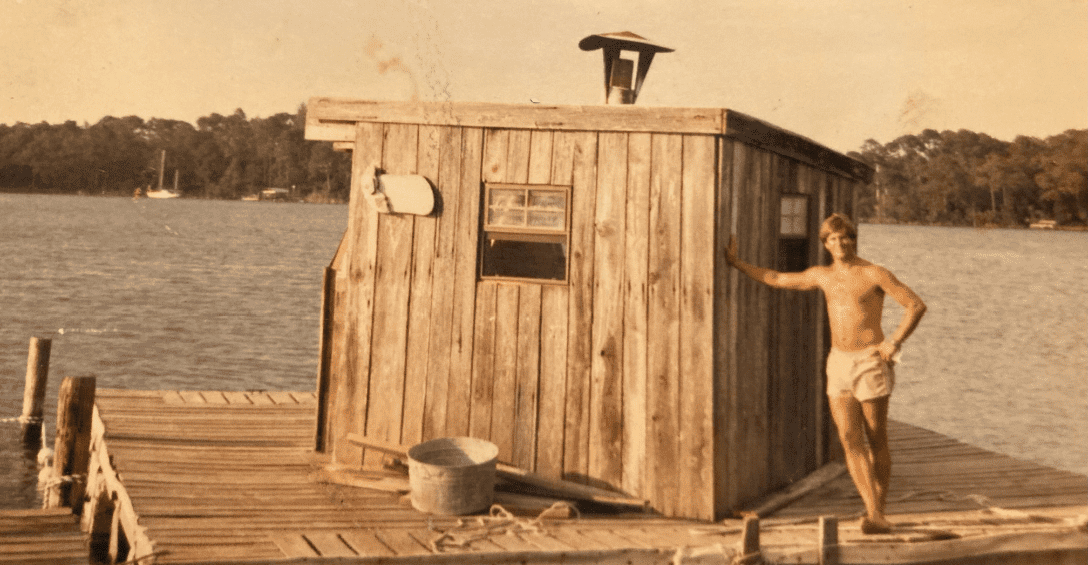

Saunas were proven aphrodisiacs, and that’s all the fuel we needed. Before we invented the Flauna, we built a ramshackle sauna made from well-used plywood and a pot bellied stove. We were in business. I remember driving the last few nails into that sauna after the sun had set. With flashlights in our mouths and a few revved-up femmes waiting impatiently, we were motivated. Sweat flowed that night.

We placed the shanty fifteen steps from the bay for a three-second sprint to the 50-degree water. After a full body immersion, we’d stand on the beach naked and marvel at the steam rising off our bare skin. We’d be relaxed to the max on rubber legs. This was generally followed by a giggle session. The hot/cold/hot/cold rush was our spiritual orgasm—a rebirth and a cleansing of the body and soul. And God knows we needed it.

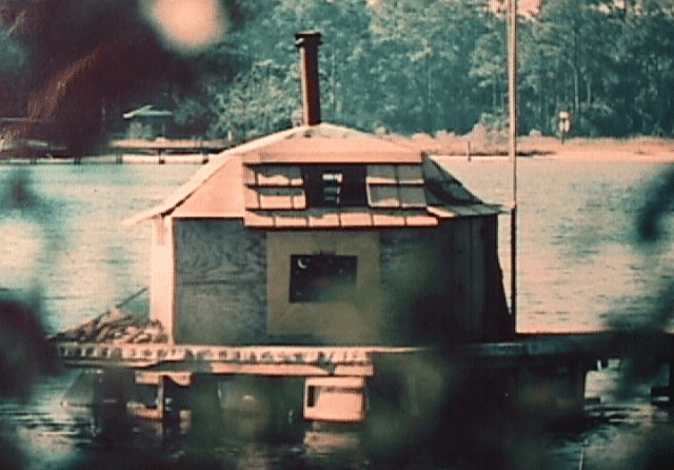

Scenic Soldier Creek

Flauna circa 1981/1982 floats serenely in Soldier Creek after various alterations had been made. Roof was raised slightly to accommodate taller sweaty peeps, styrofoam added to the middle to support more weight, corner barrels turned vertical and boxed in for stability, a smattering of shingles for good measure and the yellow Flauna flag hanging on the wall instead of the flagpole signifying that no one is onboard.

Finding the perfect location for the original sauna in which illicit acts may occur from time to time, takes careful planning. It has to be next to deep water but remote enough for privacy. Planting it next to the putting green at a country club wasn’t in the cards, even though those places have wonderfully enticing swimming pools. No, we had to find the right blend of cool water, seclusion, and an ample supply of free wood for keeping the stovepipe red hot.

Fortunately, for our little tribe, we had the prime location—a spit of sand that had been our playground since birth. We just called it The Point because it’s a sandy peninsula that stretches out in the water like a long, crooked finger. The Point had a couple of old wooden piers, a diving board, and some buoyed ropes to define the swimming area. This kept the youngsters from venturing too far from safety, and I always believe it allowed the jellyfish to target us easily.

During daylight hours, the beach buzzed with wholesome family activities—kids learning to swim, practicing their dives, or playing Marco Polo. By night, The Point was bonfire heaven where rights of passage—first kisses, first beers, first puking onto pine cones—was as common as fireworks on the 4th of July.

So, it didn’t take long for our squishy but nonetheless hard-working brains to settle on The Point as home base for the sauna. And for those few months of winter, we were unchallenged by any kind of moral authority. Family beach outings were non-existent during cold months. However, as warm weather began to creep in, a few of the conservative Point Club members—it is a private club, after all—pointed out the inconsistency of family activities and naked 20-somethings running out of what looked like a squatter’s shack with a rusty stovepipe jutting out of the wall.

We were kindly but adamantly told that the sauna had to go. No committee meetings, no vote of the board of directors. Just get rid of the eyesore. Immediately.

After an exhaustive yet unsuccessful search for a new sauna location, we (in our great wisdom) decided to burn the whole thing down. A gallon of gas and a match were a lot less effort than crowbars and hammers and hauling shit away. So we removed the old stove and pipe and set the shack aflame one last time. Wonderfully incriminating stories burned away into the atmosphere. Ashes to ashes, dust to dust.

As we watched the flames dancing into the sky, we strummed our guitars and sang “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” Our visions of glistening female shapes in the faint glow of a wood-burning stove were fading, and the old cotton-picker’s tune softened our depression.

Maybe the more accurate adage is that depression, as well as necessity, bless the bosom of invention because before the flames died we had solved our problems. After reviewing and rejecting a dozen or more locations for a new sauna, the idea came to us as if the Great Spirit had summoned Black Elk himself to deliver the sacred message.

“I’ve got it,” one of us said. “A floating sauna.”

“Brilliant,” we replied in unison.

“We can anchor it right here in Soldier Creek.”

“And move it from dock to dock.”

“Or set a mooring of our own.”

“We can hide away in a secret cove.”

“A party barge with a sauna on top.”

“That’s it!” we all shouted with joy. “A floating sauna.”

“It’s like we’re creating our own sovereign nation.”

“The country of Sauna!”

We stood in blissful silence for a few moments, stunned by our collective creative thought. Our minds reeled with the possibilities—mostly fantasies of more girls and privacy from surprise intruders. Then, like a voice from the heavens, someone said it. “Flauna.”

We let the name sink in. Floating sauna…Flauna! That was it. Soon, we were dancing around the sauna’s fallen embers chanting in unison, “Flau-na, flau-na, flau-na…” Our vision quest continued.

Flauna Dogs With Real Dog

Fully operational Flauna with the wild tube and Dawgs real dog, How Ya Been? (Ben). Fleetwood, with head poking through the window, Robert once again on roof, Dawg and Willie B. MD (in green scrubs).

On September 12, 1979, Hurricane Fredrick ravaged the coastline from Mobile to Pensacola spawning multiple tornadoes and wind gusts of more than 200 miles per hour. Thousands upon thousands of trees were downed. Every home was damaged to some extent and many simply evaporated. The term “slabbed out” became common vernacular, meaning nothing but an empty concrete slab remained where the home once stood. Near the mouth of Mobile Bay, Dauphin Island—a long string bean of a barrier island—was split in half. Where fancy beach homes once stood, a canal dissected the island. Everyone had harrowing stories to tell. One, about a woman who lost her home, was strangely poetic. When she returned to her property, her house was gone. It had completely vanished. But another house—a bigger one than before—was perched askew on her property. She jacked it up, leveled it out, and lives there still. She was the fortunate exception.

The docks and piers, which once protected boats of all sizes, were gone. Remnant pilings looked like miles and miles of crooked teeth jutting from the shoreline. One might joke that missing teeth was an appropriate image for Alabamians. It would not be funny.

For many, the disaster shattered their dreams. For others, it presented opportunities to clear fallen trees, repair roofs, and, of course, rebuild piers. My cousin and I quickly formed Perdido Bay Pier Builders and went to work. Our access to treated wood and power tools propelled the Flauna dream into reality.

We conceived, designed, and built the Flauna in one weekend—just four dudes, an overabundance of wood, a few hammers, crowbars, and one overworked circular saw. The sketched-out design called for a 20-foot by 20-foot floating deck with a 10-by-10 plywood sweat lodge in the middle. We rotated the building 45 degrees to create a diamond in a square effect. No particular reason, it just felt right. Plus, we were obsessed with 45-degree angles. If the question of angles ever came up, we always just said, “make it a 45,” and that was the end of the discussion. That resulted in a ceiling height of less than six feet, which fit three of our four Flaunaites but served up a few head knocks and cricked necks for our longer friends.

The floatation seemed simple enough. We positioned sixteen 55-gallon plastic drums around the perimeter to provide maximum stability. That it did. But our engineering was seriously flawed. All of the weight—both the sweat house and all of the naked people inside—were in the middle. Floatation on the edges and weight in the middle was a physics experiment gone awry. When fully loaded, with say, 15 steaming bodies inside, the entire Flauna deck bowed up like a slice of melon.

With the assistance of a boat lift and some strong legs, we were able to jam a few barrels toward the center of gravity and achieve a semi-level platform. Months later, we added chunks of Styrofoam during one of the many Flauna remodeling sessions. And eventually, she floated proudly, although not quite as perfectly as a bubble in a level.

The Flauna Era had officially begun and the legend grew exponentially. “Flauna Party” became a term often used. Scores of young adventure seekers were baptized into the community. Outlandish stories piled up. Lives were changed. Relationships were formed. Many were saved. T-shirts were printed. Responsible adults wondered how much further our generation could tumble into the abyss. Others were impressed by our ingenuity and creativity. Some wanted in but were afraid to ask.

Our core foursome earned a bit of celebrity. Me, Robert, Willie B., and David, known as The Dawg or just Dawg were dubbed the Original Flauna Dawgs. We’d built the thing. We named it and we hosted many humdinger Flauna Parties. After our first weekend of unabashed nakedness and profuse sweating with dozens of bold souls who joined in, we realized we had birthed an instant classic. The snowball was rolling, gaining momentum, and sucking up everything in its path. Our Field of Dreams was happening in front of our blurry eyes. And folks definitely came. In droves.

We lived in the moment, knowing that our Peter Pan lifestyle would eventually end and we’d have to grow up and, God forbid, become employed. Willie B., despite his thick-as-gumbo, Mobile, Alabama, southern accent and jet black hair down to the middle of his back, entered medical school. His nickname morphed into Willie B., MD. Robert had his eyes on the ministry and a new kind of spiritual fulfillment. Dawg’s love of flora and fauna led him into shaping the earth into beautiful, native landscapes. I pursued journalism and became a sportswriter for a daily newspaper, back when those were still around.

Time clicked on and life happened. We all got married, had kids, and began earning money in semi-respectable ways. Willie became a radiologist, Robert a minister, David a horticulturist, me a writer. As our lives became more complicated, the Flauna sat dormant, floating only on memories. We knew there was only one thing left to do.

More than a decade after we had initiated our floating wonderland, the four of us met at the Flauna on a cold winter night. We cranked her up one last time and stoked the fire until the stovepipe glowed bright red, the candles melted, and salty sweat flowed from every pore. Once again, the cleansing was the medicine we needed. We plunged into the chilly water, returned to the hot box, and repeated the process until our minds and bodies were one with the universe.

Most sentences that night began with “Remember the time….” We laughed, shed a few tears, and realized that the bond of our unbreakable friendships had been forged in a floating shack. With heavy hearts, we cranked up the boat and dragged the Flauna into the middle of Perdido Bay. Like we’d done with the original sauna, we set the Flauna aflame. A Viking funeral was the only appropriate way to end something that had impacted our lives in such deep ways.

As we eased away in the boat, we saw images of our youth dancing in the flames. We talked about Flauna 2 and the design improvements we’d make. Decades passed, and we never got around to recreating it.

Even now, decades later, one of us will be in a store, on an airplane, walking down the street, or maybe in church and someone will walk up with a silly smile and just say, “Flauna.” We’ll barely remember each other, but the wild nights in the floating sweatbox are tattooed on our brains.

You’d think a random meeting like that would spawn stories about the time we drank this or burned that. Instead, it’s usually just a silent stare, knowing that we shared a unique and bizarre life lesson. Nothing needs to be said because, well, we’ve forgotten the details of what happened anyway. Damaged brain cells have long since passed into the abyss, erasing information no one wants near their resumé or the tender ears of innocent children.

The thing is, we were kids. We did crazy-ass shit. Somehow no one died. We were better off for it but also content to let the memories fade in oblivion to bury secrets and to protect the guilty.

Scenic Soldier Creek

The original Flauna Dawgs taking a short liquid encouragement break during construction. Left to right: sitting, The Dawg; sitting on the roof, Robert; standing, Willie B. and Fleetwood. In the background, David Knowles, future honorary Flauna Dawg.

Songs are born of inspiration. They come from love, heartbreak, death, political strife, riots, police brutality, bad breakups, friendship, jealousy, or, as with every country song, good ole drankin’. Without question, alcohol stokes the creative genius of songwriters. And then it drags them down to rock bottom.

Inspiration was the fuel that led to “The Flauna Song”—a simple, three-chord ballad that pretty much tells the story. Best sung around a campfire where out of tune voices and guitars are more palatable, “The Flauna Song” quickly became an integral part of the legend. So, without further ado, here she is.

The Flauna Song – by Fleetwood and the Dawg, with help from Willie B. and Preacher Robert

Key of G – moderate beat

It was 1980 in the Month of May, been drunk on beer all day.

Getting tired of those old time games, we began to dream of those floatin’ flames.

So cut that wood and come on in, we’re gonna do some Flaunain’.

Smoke stacks getting so red hot, fire is shooting right out the top.

Gonna get as hot as we can get, gonna work up a Flauna sweat.

So grab that girl and come on in, we’re gonna do some Flaunain’.

Well the Flauna flag is flying high while the ping pong ball lights up the sky.

Life is full of mystery, but the Flauna is reality.

So stoke that fire and come on in, we’re gonna do some Flaunain’.

Jumped in that water my body turned blue, did I see God or did I see you.

Everything is spinning round, it’s time for us to get on down.

So chug that beer and come on in, we’re gonna do some Flaunain’.

I hear a boat driving up, grab some wood and stoke it up.

Must be coming from the FloraBama, oh yeah, oh yeah, wham a jama.

They got some Stoli’s so come on in, we’re gonna do some Flaunain’.

It’s been all night we’re lying on the top, Lord or Lord did we get hot,

Rubber legs are gonna take us in, after all this Flaunain’.

Slept so good till the sun went down, now it’s time for another round.